Voltage drop is calculated using Vd = (2 × L × I × R) / 1000 for single-phase circuits. But knowing the formula is the easy part. Knowing when it matters—and what happens when you ignore it—could be the difference between a happy customer and a lost contract.

Here's a real story that cost one contractor $8,000 and his reputation.

The $8,000 Lesson: When Skipping the Calculation Costs Everything

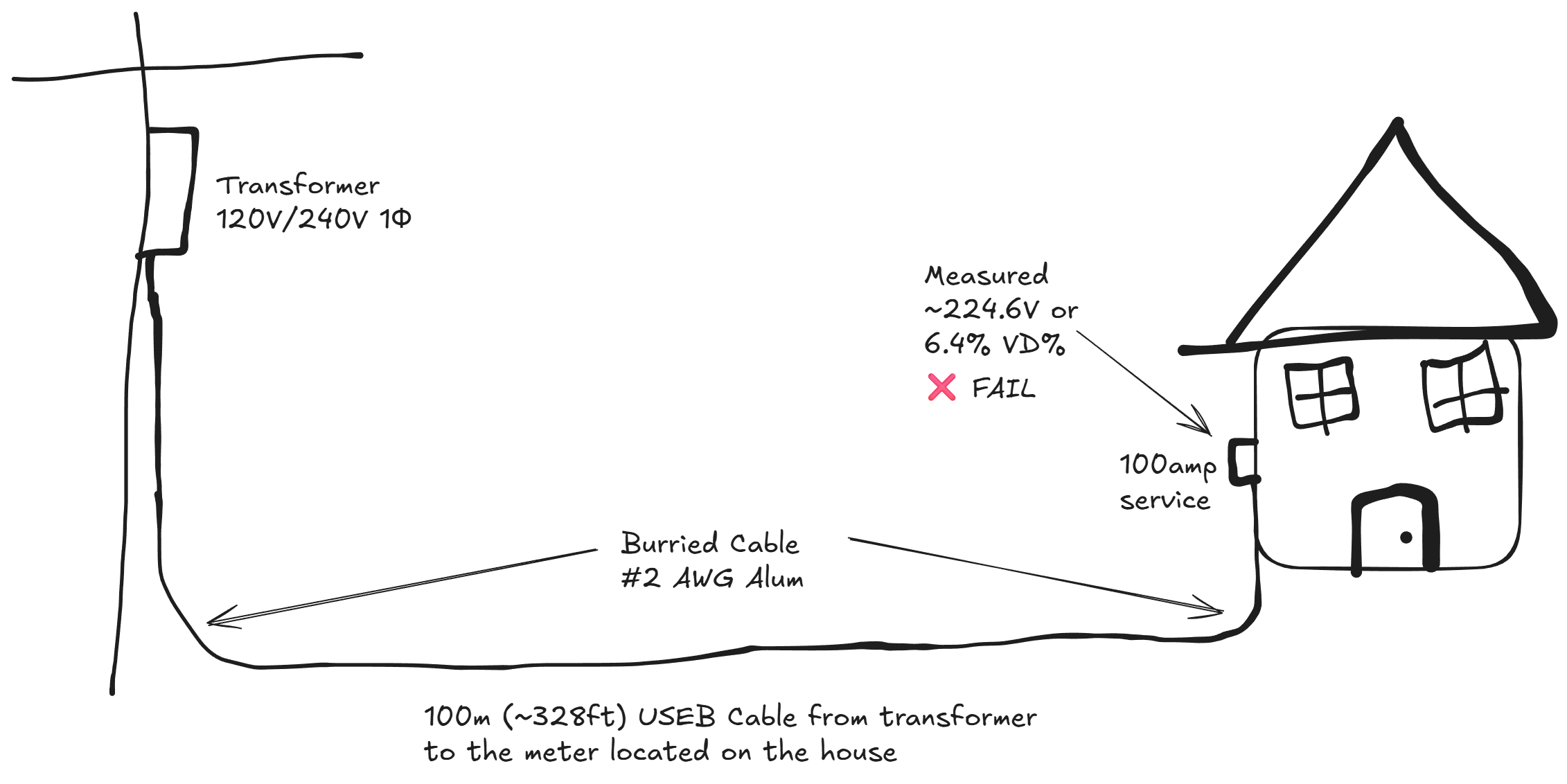

A contractor landed a new residential build. Standard stuff: 120/240V single-phase, 100A service. The meter base sat about 100 metres from the transformer—a long run, but not unusual for rural properties.

He pulled #2 aluminum URD. Sized for ampacity, it was fine. The install went smooth. Inspector signed off on the final inspection. Homeowners moved in.

Then the calls started.

Every time they ran the dryer, the lights dimmed. It was noticeable, which made the whole house feel wrong. They lived with it for a few weeks, figured maybe it was normal for a new build. It wasn't.

They called the utility company. A technician came out and measured voltage at the meter. What should have been 240V was reading somewhere around 216-224V under load. The 120V legs were showing 108-112V. Way below nominal.

The utility kicked it back to the contractor.

#2 aluminum. 100 metres. 100 amps. The math doesn't lie:

Voltage drop: 6.33%

CEC Rule 8-102 allows 3% for feeders. This was more than double the limit.

The contractor had to trench the entire run again, pull new cable, and upgrade to #4/0 aluminum, which passes at 2.00% drop.

The damage:

- $8,000+ in materials and labor to redo the run

- Lost the builder contract—this affected the relationship between the electrician and developer

- Reputation hit in a market where word travels fast

The irony? A 15-second calculation on his phone would have caught this before the first shovel hit the ground.

How to Calculate Voltage Drop: The Formula

Here's the math that would have saved that contractor eight grand.

Single-Phase:

Vd = (2 × L × I × R) / 1000

Three-Phase:

Vd = (1.732 × L × I × R) / 1000

Where:

- Vd = Voltage drop in volts

- L = One-way conductor length (feet for NEC, metres for CEC)

- I = Load current in amperes

- R = Resistance per 1,000 feet (NEC) or per kilometre (CEC)

Why the "2" in the single-phase formula? Current travels to the load and back. Both conductors have resistance. For three-phase, the geometry changes—hence √3 (1.732).

The resistance value is where people screw up. You can't guess it. You need the actual table values:

- NEC: Chapter 9, Table 8 (AC resistance at 75°C)

- CEC: Appendix D, Table D3 (resistance in Ω/km)

Aluminum has higher resistance than copper for the same gauge. Steel conduit adds slightly more resistance than PVC due to magnetic effects. Use the right values for your installation.

Or skip the manual math entirely and use the calculator.

Let's Do the Math: Why #2 Aluminum Failed

Let's run the exact calculation from that $8,000 job.

The Setup:

- System: 120/240V single-phase

- Load: 100A (full panel rating)

- Length: 100 metres one-way

- Conductor: #2 AWG Aluminum URD

- Resistance: 0.76 Ω/km (CEC Table D3—aluminum uses copper values two sizes smaller)

The Calculation:

Vd = (2 × 100 × 100 × 0.76) / 1000

Vd = 15.20V

The Percentage:

15.20V ÷ 240V = 6.33%

CEC Rule 8-102 allows 3% maximum for feeders. This install was running at more than double the limit. Fail.

Now let's see what should have been installed.

Upgraded to 4/0 Aluminum:

- Resistance: 0.24 Ω/km

The Calculation:

Vd = (2 × 100 × 100 × 0.24) / 1000

Vd = 4.80V

The Percentage:

4.80V ÷ 240V = 2.00%

Under the 3% limit. Pass.

One practical note: 3/0 aluminum would technically work for this run, but good luck finding it. URD cable manufacturers don't commonly stock 3/0—it's an odd size. Call your supplier before you spec it. They'll steer you to 4/0, which is readily available and gives you margin anyway. Note: This job was completed when #2 aluminum was acceptable for a 100A residential service.

NEC vs CEC: Know Your Code

If you're working in the States, you might be thinking "I've seen plenty of installs over 3% that passed inspection." You're not wrong. Here's why:

| Code | Type | Feeder Limit | Branch Limit | Combined Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEC | Recommendation | 3% | 3% | 5% |

| CEC | Mandatory | 3% | 3% | 5% |

The NEC voltage drop limits appear in Informational Notes—specifically 210.19(A) Informational Note No. 4 and 215.2(A) Informational Note No. 2. These are recommendations, not requirements.

CEC Rule 8-102 uses the word "shall." That makes it enforceable. You will fail inspection in Canada if you exceed these limits.

But here's the thing: the equipment doesn't read code books. A motor running at 6% voltage drop is going to run hot regardless of which side of the border you're on. The limits exist because undersized conductors cause real problems—dimming lights, overheating equipment, premature failure.

Design to the limits. Your callback rate will thank you.

How to Never Make This Mistake

Five things that would have saved that contractor:

1. Calculate before you quote. Voltage drop affects material cost. 4/0 aluminum costs more than #2. If you don't run the numbers before pricing the job, you're either eating the difference or going back to the customer with your hand out.

2. Use actual table values. Rules of thumb will burn you. Aluminum isn't copper. Steel conduit isn't PVC. Temperature matters. Pull the actual resistance from NEC Table 8 or CEC Table D3.

3. Size for the breaker, not the expected load. That 100A panel might only see 60A on a typical day. But you size conductors for 100A because that's what the system is rated for.

4. Verify before you trench. Underground runs are brutal to redo. Fifteen seconds with a calculator beats fifteen hours with a shovel and a string of profanity.

5. Document it. Screenshot your calculation. When the inspector asks—and on a long run, they will—you've got the answer ready.

The old saying applies: measure twice, cut once. Except here it's calculate twice, trench once.

Voltage Drop FAQ

What is an acceptable voltage drop for a residential service?

NEC recommends 3% maximum for branch circuits and 5% maximum for feeder plus branch combined. CEC Rule 8-102 makes these mandatory limits. For a 120V circuit, 3% equals 3.6V—so your voltage at the load should be at least 116.4V.

Does voltage drop matter for short runs?

For runs under 50 feet at typical residential loads, voltage drop is usually negligible. But always check for high-current circuits—EV chargers, ranges, heat pumps—or when using aluminum conductors. The higher resistance adds up faster than you'd think.

How do I reduce voltage drop without upsizing the wire?

You've got a few options. Increase the system voltage—240V instead of 120V cuts current in half, which proportionally reduces voltage drop. Shorten the run by relocating the panel closer to the load, if that's feasible. Or switch from aluminum to copper, which has lower resistance for the same gauge.

Why do lights dim when the dryer runs?

This is the classic symptom of excessive voltage drop on service entrance conductors. The dryer draws high current (often 25A or more), which increases voltage drop across undersized conductors. That leaves less voltage available for everything else on the panel. If you're seeing this, have the service entrance conductors verified—there's a good chance they're undersized for the run length.

Is voltage drop a code violation?

In the US under NEC, voltage drop limits are recommendations in Informational Notes, not enforceable requirements. In Canada under CEC, Rule 8-102 uses "shall"—making the limits mandatory and a legitimate fail point on inspection.

What's the difference between voltage drop and voltage loss?

They're often used interchangeably in the field. Technically, voltage drop refers to the reduction across a specific conductor or component, while voltage loss sometimes describes energy dissipated as heat. For practical purposes, they mean the same thing: your load isn't getting full voltage because some of it is being eaten by conductor resistance.

Don't Learn This the Hard Way

That $8,000 mistake took hours to fix and fifteen seconds to prevent.

The formula isn't complicated. The table values aren't hard to find. The calculation takes less time than making a coffee.

There's no excuse for guessing on voltage drop—not when the math is this simple and the consequences are this expensive.

Calculate Your Voltage Drop Now →

Works on your phone. Works offline. Shows the formula so you know exactly what you're getting. Bookmark it on your phone for easy access!

Built by a 25-year journeyman who's seen this mistake more than once.